As we head towards the so-called “second wave” of COVID-19, Italy is no longer at the forefront of the disease. Indeed, while back in March we led the sad tally of infections and deaths, we were also the first to enforce a country-wide lockdown. That, coupled with the shock from what we were seeing, made people accept and follow the rules. This is not something anyone took for granted: Italians have a strong tendency to disregard authority, but the worst that happened at the time was that couch potatoes claimed they needed to go out for a run, or something to that effect. We didn’t even hoard toilet paper, undoubtedly thanks to the ubiquitous presence of bidets, however we did hoard flour and baker’s yeast; pizza and bread were made and eaten, for if life is short, then carbs are the way.

The serious lockdown worked wonders for Italy, but then came the summer. As businesses slowly reopened and people were let out of their alleged houses-turned-cages, many forgot that the virus was still going around. I remember the day we had less than a thousand new cases: it did feel like victory, and I recall writing something like “Can we not mess this up, please?” on my personal Facebook profile; heart reactions only. We had made it. We had beaten the virus, scores of deaths notwithstanding. It felt good. Almost too good. People started traveling, meeting up, partying. Yet that dreaded word we had learned during the lockdown, assembramenti, echoed and lingered. It means gatherings, but with an ominous undertone of a shapeless mass of people all clustered together, the kind of thing that could turn into a stampede in the blink of an eye.

But it felt good to be out, and life was good. We had won. We watched the news reporting from other countries, and we felt good about ourselves. Look at the United States, how they managed to politicize even something as basic and obvious as face masks in the middle of a planet-wide pandemic. We conveniently forgot that several of our own politicians had been politicizing everything about the pandemic as well, but hey, we had won. Look at Brazil, how many people are getting infected because they believe the lies that Bolsonaro spreads. Look at the United Kingdom, bet they didn’t see this mess coming on top of Brexit, now did they? Look at Sweden, with their crazy plan for herd immunity. Why doesn’t everyone else enforce a full lockdown? We did it, and we won. It’s so easy. Campioni del mondo, campioni del mondo.

Then the summer season did that annoying thing that it’s been doing for time immemorial: it yielded to autumn. A few countries in Europe began counting more and more cases. Spain and France, especially, but not just them. They had all entered lockdown after us back in March, and in some cases left it earlier. Of course they’re having more cases, many of us thought: they didn’t learn the lesson. They didn’t win like we did. To tell the truth, they didn’t lose either: they did manage to flatten the curve, unlike other countries where the first wave effectively never ended. But they were falling for it again. That surely won’t happen to us, we told one another, to reassure us that the newly-rediscovered “old world” would not be taken away from us once more. After all, we won. We had won.

Come September. Schools reopened. People went back to work full time. Buses and trains and subways and trams were ridden. Like the first few snowflakes that slide over one another before eventually turning into an avalanche that destroys anything along its way, we dismissed the early signs. It’s inevitable, it’s expected. It’s physiological, a word we commonly use in Italian to describe something typical and unsurprising, completely oblivious to the irony of using it in this context. But as more and more calls for caution came from experts, louder and louder grew the complaints from both leaders and everyday folk. We can’t afford another lockdown, some said. We can’t let people die in the name of the economy, others replied. If we don’t die from the virus, then we’ll die from starvation, others still interjected. Those who had been pushing hoaxes and conspiracy theories, whether through ignorance or malice, or perhaps both, were having a field day spreading uncertainty and fear.

All the memories about the reasons behind the spring lockdown suddenly seem to have been forgotten by most. Many only remember that we went through that, and that it was difficult. But they forgot why we did that in the first place. They now feel that they were the true heroes for staying home watching Netflix all day, yet at the time they cried for the front-line doctors and nurses who risked their own lives to fight the actual fight. They now feel sick at the thought of being stuck inside for a few weeks again, yet at the time everyone’s biggest fear was for a relative to be hospitalized, because that meant not being able to even say goodbye if things were to take a turn for the worst. They now want their old life back because they had one more taste of it, yet in March they dared not even think about the future, as the news on TV mercilessly showed military trucks carrying the dead from hospitals to cemeteries.

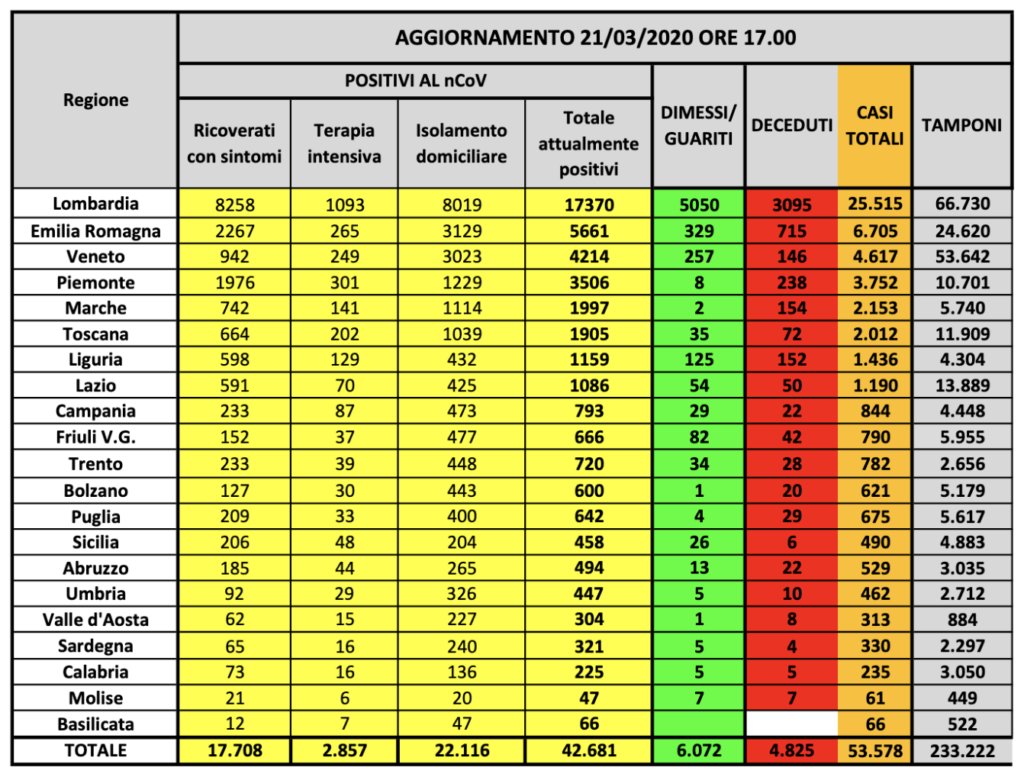

As I’m writing this, Italy has had just below 20,000 new cases a day for two days in a row. Certainly a far cry from France and Spain’s situation, but these numbers double every week or so. Restrictions are coming, and a Christmas lockdown cannot be entirely ruled out. A few politicians are already going for it, which I personally find baffling — I have long given up any religion, but I distinctly remember being taught that God is everywhere (for better or worse), so that not being able to go to church really makes no difference if you’re a true believer. But that is beyond the point. The point is that things are going to take a turn for the worse soon, as more cases in general mean more serious cases, and more serious cases mean more hospitalizations, and more hospitalizations means more people in intensive care, and more people in intensive care means that eventually someone will not find a spot, and not having enough spots means that choices will have to be made about who gets to take those available spots. Some readers will undoubtedly be thinking that I am perversely enjoying writing such things, but believe me you, I find absolutely no enjoyment in saying these things, and indeed am extremely concerned about my own family. There is nothing I wish I could do more than reboot this timeline. But I learned long ago that pretending that everything is fine when everything is actually on fire only prevents proper planning and action. It’s just how it is, and me not liking it won’t make one iota of difference.

It would be easy to blame the young who want to meet their friends, or say that schools should have been reopened more carefully, to explain the current situation. But there’s no single cause of fault here. The simple fact is that the world has changed, and that until a vaccine comes out, things are going to be different. And that is assuming that a vaccine does come out and is effective in the long term. It’s not the first time that something comes along and changes everything for everyone. The World Wars, the fall of the Berlin Wall, 9/11 and more all come to mind. Yet those were all things that we, humans as a species, brought on. This is different, this is us that we were all collectively forced to deal with, and we don’t even know how long it will take. That’s what makes it hard to accept. (I won’t even entertain the concept of this virus being made in a lab, any more than I entertain the idea of airplanes leaving “chemtrails”: just like all pilots must eventually land, so has this virus hit everywhere.)

It is only natural to crave and pine for what we lost. Yet what needs to be done is to look ahead, even though it may not be easy, and it certainly is not. Had we accepted all of this sooner, had we not deluded ourselves into thinking that the worst was behind us, we may have avoided this. We thought that we had won, and we had; but we mistook the battle for the war, and cheered way too soon.

What concerns me is that, even as the numbers climb, many are still acting cocky. Just one example: a rule was made here for businesses to close at midnight, to prevent those alcohol-fuelled gatherings that are more likely to happen at night than during the day. A few businesses owners shut down at midnight as expected, and then opened again at five minutes past midnight. Perfectly legal, for sure, since the decree did not set up a time for reopening, but what does that accomplish beyond a few headlines and pats on the back for “standing up against the system”? What these people fail to see is twofold: that this is not a game of force, rather a game of strategy; and that this is about everyone, not just them individually.

Things are going to get worse before they get better, and if history has taught us anything, is that any pandemic’s second wave is usually worse than the first. We do have one huge advantage, however: we have statistics, science and data on our side. That’s unprecedented, and could make the difference in getting this disease under control more effectively and quickly than any other. We could coordinate efforts on a global scale. All it takes is to look beyond petty interests and disagreements, and work together on all levels: from governments sharing information and planning responses and reactions, to all of us wearing masks and practicing basic hygiene, if we really cannot avoid going places.

This virus, this enemy, this thing that we cannot see yet has managed to overthrow our sense of normalcy, it can only spread if we physically stay within reach of one another. That is its strength, for losing that makes us feel like we are not ourselves anymore; we are social animals, after all. And even thought our global, small world has sped up the spread of this virus, it also means that we have our cumulative, global knowledge to use against it.

Let us not fool ourselves: this winter — or summer, if you’re south of the equator — will not be easy. During the (first?) lockdown, Italians loved saying and writing “andrà tutto bene”: everything will be alright. It will, eventually. But they also kept saying “io resto a casa”: I’m staying home.

This is not something that the governments, the powers that be, the big guys can handle on their own. Our very actions can and do make a difference.

So I’ll ask for a favor once again.

Can we not mess this up, please?