As I mentioned in my previous post, I haven’t been on social media much ever since September 2021. Personal issues just took priority, and I decided to take a break from all the negativity I was subjecting myself to. I will talk about that in another post, as I still want to resume writing more or less regulary; it’s just that I’ve been quite busy with everything, so I haven’t had much of a chance to do so.

Still, if anyone who had me on social media is wondering how things are around here, with the war in Ukraine and everything: I’m fine, we’re fine. Sort of.

I’ve always considered myself European first and foremost, much more so than I’ve considered myself Italian. For me, “here” means Europe. And to get news about war taking places “here” is scary, concerning, disheartening. It’s also disappointing to see that the choices made by the European Union during the past decade with regard to the eastern situation were, well, pretty much wrong, to put it mildly. Then again, how should have that been played? Should sanctions have been applied when Russia invaded and claimed Crimea? Should fighter jets have been shipped to the area? I honestly don’t know, I genuinely have no idea. And “ifs” and “buts” can’t change history.

The fact remains that war is here and it’s something that I would have never expected. This may come as a shock to USians but we’re not used to wars, and most EU countries not only don’t even have conscription anymore, we also don’t have a fetish for the military. See, when your whole continent is wrecked by two destructive wars in the span of three decades, you realize that maybe that’s not best approach to things.

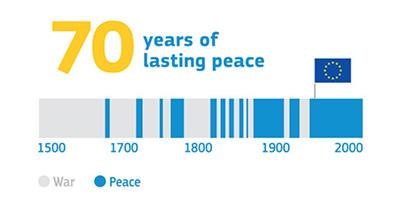

Back in 2015, this graph was shared by the European Union itself:

Yes, that’s a bit simplistic and self-celebratory. Yes, we did have the Yugoslav wars, which had their fair share of war horrors including genocide. Those were terrible, there is absolutely no denying that, and I will write about my own memories of those in a subsequent post. However, it’s worth pointing out that the whole idea of Yugoslavia was always complicated, and it was probably inevitable that it would end like that. Still, we also very recently had countries splitting up quite amicably, such as Serbia and Montenegro in 2006.

For many of us, especially those from my generation who grew up with the idea of Europe being united, seeing those images from Ukraine evokes a sense of uneasiness. We feel powerless, and we think about all the documentaries we saw of our own countries looking like that less than a century ago. Comparing Putin and Hitler is a futile exercise: they’re different in many ways, yet their actions are similarly wicked; if not in scale, for their effects.

It’s honestly difficult to explain how I, and many others, feel. It seems like history has sped up considerably. Lenin, of all people, famously said that “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen”.

Countries like Germany and even Switzerland have abandoned their traditional pacifism to back sanctions. Several eastern countries, that is Ukraine, Moldava and Georgia, have formally applied to join the European Union. Ukraine’s own president regularly posts heartfelt appeals to the international community to do more. Meanwhile reports of war crimes keep coming: Russian tanks crushing civilian vehicles, shooting on supposed humanitarian corridors, bombing cities despite an alleged ceasefire, and shelling children’s hospitals.

And amidst all of that, regular Russian citizens, the vast majority of them, people like me writing and you reading, are jailed if they dare protest. And many people, the older generation especially, doesn’t know or believe what’s happening; and that’s not just in Russia, it’s happening even in Ukraine.

One word I’ve seen mentioned time and time again in these last few days, in posts and tweets and reports from and by people living there, is “brainwashing”, or even “state brainwashing”. It seems surreal at a glance, but think about all the fake news and hoaxes that people believe where you live. Think of how much easier covid could have been handled if only dangerous hoaxes hadn’t swept the planet worse than the virus itself. Think of Orwell’s “1984”. Think of Fox News in the US, or Mediaset’s newscasts in Italy. Is it really that hard to believe that people can be brainwashed when a single entity controls the media?

When I was in high school, the topic of media control came up. I can’t even remember the context, or even the teacher; I think it may have been the last Electronics teacher I had, because he was prone to going off on a tangent and talking about technology’s role in society (during my final state exam, he asked me about how the invention of transistors changed warfare; he didn’t even ask me about transistors themselves, he just wanted me to go philosophical.) Well, he said something about the media that I had never thought about. He asked: when a coup d’état takes place, what’s the first thing they try to seize control of? In our naïve teenage innocence, we confidently replied: the parliament. It makes sense, right? He shook his head, smirked, and said: no, they seize the media. The TV towers, the radio stations, the newspapers. Again, look at how wildly different narrative is in your native country, depending on which newspaper you read or what newscast you watch. People consider the media as inherently authoritative, so if you’re taking control of an area, you want to make sure that the only authoritative voice is yours.

And yet, while new technologies inherently promote the diffusion of fake news, they can also provide a way for information to spread when everything else seems to fail. It takes a lot of effort to tell what’s real and what isn’t, especially when time is short, people are literally dying, and it’s very easy to fall prey to emotion.

I don’t know how long this war will be. It’s clear that Russia expected this to be quick, and it didn’t go as well. This video explains some of the reasons, but keep in mind that things are happening very quickly and nothing is always as easy as it seems. Even “Putin is just crazy” doesn’t work, as a former Russian minister clearly explained.

I don’t know if the war will expand west, which is almost certain if a no-fly zone is declared in Ukraine. I don’t know what will happen if nuclear weapons are used by any party involved (or not yet involved). I don’t think anybody knows and, again, to know that this is happening “here”, in Europe, is scary at such a subconscious level that it’s hard to explain.

And — forgive me if I’m going to be more direct from this point on — what’s even harder to explain is how stupid it all seems when you take a step back and look at the bigger picture. Everyone’s got their arguments, and everyone’s right from some point of view or another. But then you see pictures of a woman in labor being evacuated because a maternity hospital has been bombed and there are dozens of children and newborns feared dead under the rubble, and pictures of dead people being buried in a trench turned into a mass grave, and you realize that we’ve just fucking failed as a species. Homo sapiens, human’s scientific name, means wise man. Sapiens my ass.

We talk so much of colonizing the universe, of tuning our bodies to rid us of disease, of living forever, and we can’t even be decent to one another. We hate on one another just because they were born on this or that side of a line on a map, or because their skin is a different shade, or they speak a different language. Hell, we hate on one another because they keep putting their garbage half a meter away from their designated spot and that just pisses us off and we want to strangle them for that. We are fucking stupid. All of us, collectively, as a species.

I saw a report earlier that thermobaric weapons have been used by Russia in Ukraine. I didn’t even know what that was, but I’ll spare you the search: it’s a bomb that uses fuel differently from a traditional one, so it causes more damage. A true feat of engineering, honestly. But then I read that their usage is only illegal if it’s against civilians. That made me laugh. I swear, I started laughing when I read that. How do you even enforce something like that? How do you apply rules to war? Seriously, how do you even do that? Even a declaration of war allegedly has rules, but if you’re attacking someone, why would you even care in the end?

It’s all very surreal, and overall stupid. Absolutely stupid. If we truly put our collective brains to good use, we would be doing truly great things. But we’re just a bunch of talking apes taking themselves way too seriously, so we just bomb the shit out of one another because we woke up angry.

Back in 1990 — Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union were still around — we got a picture from Voyager 1, a little spacecraft that had been floating in space for 23 years at that point. It was 6.4 billion kilometers away. There’s a tiny little spot on the right side of the picture, right through that vertical streak:

Astronomer and cosmologist Carl Sagan famously described it as follows, and I have been thinking about this a lot during the past few weeks.

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there–on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.

As we once again fear for our collective demise, it’s impossible not to wonder: will we ever learn, before it’s too late?